Researching autonomy

Researching and measuring autonomy

Most research in autonomy is descriptive or qualitative. Self-assessments and interviews are common instruments to elicit data from learners or their teachers about their perceived level of autonomy. Some people argue that autonomy can not be ‘measured’ and that determining a level of autonomy is not feasible (I myself have argued that it is more fruitful to look autonomy as manifested in learning behaviour, rather than as a static internal capacity). However, especially in general education, attempts have been made to gauge students’ autonomy. Below I have compiled some of these instruments. Some of them were taken from this website at the University of Rochester. It is important to note that some are based on more limited conceptualisations of autonomy than is usual in the area of language learning and teaching. Nonetheless they may be of use to your research, especially as some of them have been applied in a wide range of research contexts and have been extensively validated. If you know of any others, please do let me know!

Hayo

Index:

The General Causality Orientations Scale

Academic Self- Regulation Questionnaire

The Learner Autonomy Profile (LAP)

The Inventory of Learner Desire (ILD)

The Inventory of Learner Resourcefulness (ILR)

The Inventory of Learner Initiative (ILI)

The Inventory of Learner Persistence (ILP)

The Appraisal of Learner Autonomy (ALA)

Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale

Self-Regulation Questionnaires (SRQ)

Metacognitive awareness questionnaire

Intrinsic Motivation Inventory

The Awareness of Independent Learning Inventory

Perceived Autonomy Support: The Climate Qustionnaires

The Self-Empowerment Index

Online Measure of Autonomy in Language Learning

The Oddi Continuing Learning Inventory

Autonomy supportive versus controlling

Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)

The Survey of Reading Strategies (SORS)

The General Causality Orientations Scale

From the website: “Deci and Ryan’s (1985a, 1985b) causality orientations theory is concerned with individual differences in the extent to which people seek to be autonomous or controlled or in the regulation of their behaviour. According to this theory, there are three causality orientations: an autonomy orientation, a control orientation and an impersonal orientation. When autonomy oriented, individuals seek out opportunities to be self-determining, regard the characteristics of events as sources of information to regulate their chosen behaviours, and regulate their actions on the basis of personal goals and interests. When control oriented, individuals rely on externally or internally imposed controlling events, such as extrinsic rewards and deadlines to regulate their behaviour. The impersonal orientation is characterised by a belief that behavioral outcomes are beyond one’s control When impersonally oriented, individuals feel that they are unable to regulate their behaviour to achieve desired outcomes, leading to a sense of incompetence and helplessness.

Deci and Ryan (1985b) developed the General Causality Orientations Scale (GCOS) to assess the strength of each of these orientations. The GCOS was designed as a global measure to indicate enduring general motivational orientations across various different aspects of life. The instrument has an unusual format in that individuals are presented with a series of scenarios addressing different life circumstances such as situations involving interpersonal relationships or the work environment. Each scenario is followed by a set of three responses corresponding to each of the three causality orientations. Respondents are asked to indicate the extent to which each response is characteristic of him or her, providing a score for each orientation.”

See: link

Academic Self- Regulation Questionnaire

The Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire assesses students’ self-reported reasons participating in school (i.e., ‘‘Why do I try to do well in school?’’). The reasons fall into one of four categories of regulation, ranging along a continuum from external (e.g., ‘‘Because that’s what I’m supposed to do’’) to introjected (e.g., ‘‘Because I’ll feel really bad about myself if I don’t do well’’) to identi?ed (e.g., ‘‘Because its important to me to do well in school’’) to intrinsic (e.g., ‘‘Because its fun’’).

A paper with information about its content validity and reliability figures is available here.

The Learner Autonomy Profile (LAP)

The Learner Autonomy Profile is licensed to Human Resource Development Enterprises and is available through its website (http://www.hrdenterprises.com/).

From the website: “HRDE has developed and validated a series of inventories designed to produce precise understanding of an individual’s level of autonomy as a learner. Completion of the five inventory battery yields a Learner Autonomy Profile (LAP). The individual’s LAP provides specific information that can be utilized to increase reliance upon strengths and overcome weaknesses related to learner autonomy.

• The Inventory of Learner Desire (ILD) — 33 items, est. 5 mins.

• The Inventory of Learner Resourcefulness (ILR) — 53 items, est. 9 mins.

• The Inventory of Learner Initiative (ILI) — 44 items, est. 7 mins.

• The Inventory of Learner Persistence (ILP) — 34 items, est. 6 mins.

• The Appraisal of Learner Autonomy (ALA) — 9 items, est. 2 mins.

Respondents need not complete more than one inventory at a time, but once each is started it must be completed in a single session. A Learner Autonomy Profile is produced for each inventory, but all five inventories must be completed before profiles can be produced.

The Inventory of Learner Desire (ILD)

The Inventory of Learner Desire assesses seven dimensions of the respondent’s world-view and view of self. The profile produced identifies issues and attitudes that contribute or detract from the individual’s capacity to form intentions related to learning.

The Inventory of Learner Resourcefulness (ILR)

The Inventory of Learner Resourcefulness assesses seven dimensions of the respondent’s intention to engage in behaviors that constitute essential resources in learning. The profile produced identifies issues and attitudes that contribute or detract from the individual’s intention to mobilize both the internal and external resources associated with learning processes.

The Inventory of Learner Initiative (ILI)

The Inventory of Learner Initiative assesses five dimensions of the respondent’s intention to engage in behaviors associated with initiation of learning processes. The profile produced identifies issues and attitudes that contribute or detract from the individual’s intention to take appropriate initiatives associated with learning processes.

The Inventory of Learner Persistence (ILP)

The Inventory of Learner Persistence assesses three dimensions of the respondent’s intention to engage in behaviors associated with persistence in learning processes. The profile produced identifies issues and attitudes that contribute or detract from the individual’s intention to persist in learning processes until appropriate personal satisfaction is reached.

The Appraisal of Learner Autonomy (ALA)

The Appraisal of Learner Autonomy assesses the respondent’s general beliefs concerning the ability to act intentionally with reference to learning activities. The scale was derived from Professor Albert Bandura’s (Stanford University) exercise self-efficacy scale with his permission.

Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale

The SDLRS was first published in 1978 by Guglielmino. It is a 58 item, five point Likert scale instrument that measures a total score for self-directed learning readiness. Delahaye and Choy (2000) confirm the internal consistency and test-retest reliability values, as well as content, construct and criterion-related validity. Guglielmino (1978) identified eleven characteristics of self-directed learners including initiative, independence, persistence, responsibility, self-discipline, curiosity, desire (to learn or change), basic skills (study and organizational), pacing/completion, joy of learning, and goal orientation.

It can be ordered here: hlink

Self-Regulation Questionnaires (SRQ)

From the website below: ‘This is a family of questionnaires that assesses the degree to which an individual’s motivation for a particular behavior or behavioral domain tends to be relatively autonomous versus relatively controlled. It includes academic (for children), prosocial, health care, learning (for adults), gymnastics/exercise, religion, and friendship. The Self-Determination Scale (SDS) was designed to assess individual differences in the extent to which people tend to function in a self-determined way. It is thus considered a relatively enduring aspect of people’s personalities which reflects (1) being more aware of their feelings and their sense of self, and (2) feeling a sense of choice with respect to their behavior. The SDS is a short, 10-item scale, with two 5-item subscales. The first subscale is awareness of oneself, and the second is perceived choice in one’s actions. The subscales can either be used separately or they can be combined into an overall SDS score.’

You can read more about it here: link

Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Implicit and self-attributed achievement motives: Concordance and predictive validity. Journal of Personality, 70, 729-755. Read it here: link

Metacognitive awareness questionnaire

Sinclair (1999) takes metacognitive awareness as a key aspect of autonomy and as the starting point for investigating students’ level of autonomy. She argues that autonomy can only be measured by subjective standards, i.e. from what the learners themselves say about it. She uses interviews to determine whether students can provide a rationale for their choice of learning

activities, describe the strategies they used, provide an evaluation of

these strategies used, identify strengths and weaknesses, describe plans

for learning, and describe alternative strategies. She also devised a set of

questions to use in the interviews. The questions can be found in the publication below:

Sinclair, B. 1999 ‘Wrestling With a Jelly: the Evaluation of Learner Autonomy’ In: B. Morrison (ed.) Experiments and Evaluation in Self-Access Language Learning p.95-109 Hong Kong: Hasald.

Intrincisc Motivation Inventory

Autonomy and Motivation are arguably closely related concepts. This scale measures students’ intrinsic motivation. You can read about it here:

Plant, R. W., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and the effects of self-consciousness, self-awareness, and ego-involvement: An investigation of internally-controlling styles. Journal of Personality, 53, 435-449. You can download it here: link

Online Measure of Autonomy in Language Learning

From the website: OMALL is the Online Measure of Autonomy in Language Learning. It is a part of a PhD project to develop a web-based instrument for the investigation of autonomy in language learners who are in, or about to start, tertiary education. There are many instruments designed to assess the way learners learn (their learning styles, strategy use, attitudes, etc.), however, there is no instrument specifically designed to research the construct of language learner autonomy at tertiary level.

OMALL consists of items intended to cover all areas of the construct of language learner autonomy. At present the questionnaire is at an early stage of development where the primary aims are reducing the number of items, refining the wording, and finding which items contribute best and which need to be changed or eliminated.Please try it, and give your feedback in the form at the end – your contribution will be invaluable in the development of the questionnaire. If your first language is Chinese, please do the New OMALL Questionnaire in Mandarin Chinese; others please do the English version.

OMALL will be particularly appropriate for language learners from backgrounds that have not prepared them for Western-style tertiary education. China, with its recent opening up to the West, is a very important instance of this. Its eventual uses may, potentially, include: indicator of broad overall level of autonomy, formative aid, diagnostic tool, and research tool to develop autonomy theory.

The Oddi Continuing Learning Inventory (OCLI)

The Oddi Continuing Learning Inventory (OCLI) is a 24-item Likert scale and measures self-directed continuing learning. (more information coming).

The Awareness of Independent Learning Inventory

An inventory of questions designed to measure awareness of independent learning. This is an interesting instrument designed for general education, so not specifically for language education, although I see no reason why it could not also be useful for that. The AILI is a list of 45 statements about learning and teaching. Respondents are asked to rate how true each statement is for them on a scale of 1 to 7. Here is some general information from the authors:

“The AILI has been designed for people from whom it can be expected that they possess substantial metacognitive qualities that are based on ample learning experiences. We use the term ‘independent learning’ to designate a type of learning and studying that is accompanied and directed by metacognition. The inventory can be used for students from all stages of higher education, regardless of their specific studies. The instrument will provide an answer to the following three questions:

1. To what extent do students, according to themselves, have declarative knowledge about learning and studying?

2. To what extent do students, according to themselves, have the skills to systematically regulate their own learning and studying?

3. To what extent do students, according to themselves, have a sensitive and inquisitive attitude towards information that is important for further development of their metacognitive knowledge and regulatory skills?

The instrument consists of 45 statements, 15 for each of the above questions. Students are asked to circle a number on a 7-point scale for each statement. The scale ranges from 1: “not true at all” to 7: “ completely true”. Optical readable forms are used for the answers. Two parallel versions of the AILI have been designed. In the A-version 23 items are presented in a positive form and 22 in a negative one (see further down). In the B-version each item that is formulated positively in the A-version is presented in a negative form and vice versa.”

The instrument is included below (apologies for the lack of formatting). A paper about this instrument was published here:

Elshout-Mohr, M., J. Meijer, M.M. van Daalen-Kapteijns, and W. Meeus. 2003. A self-report

inventory for metacognition related to academic tasks. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam,

SCO-Kohnstamm Instituut.

1 I know which assignments students really need to work at systematically.

2 I think it’s necessary to make a conscious effort to work systematically when you are studying.

3 When I’m reading something I don’t pay much attention to whether it comes alive for me.

4 I don’t think it’s important to feel personally involved in what you are studying.

5 I ignore feedback from tutors on my method of work.

6 While working on an assignment I pay attention to whether I am carrying out all parts of it.

7 While working on an assignment I keep a record of my learning aims.

8 When I’ve finished an assignment I don’t check for myself whether I’ve worked at it systematically enough.

9 I never get the feeling that an assignment has suddenly started to interest me.

10 While studying information I never get a sudden feeling that I’m beginning to gain insight.

11 I don’t think it’s necessary to make a conscious effort to gain insight when you are studying.

12 I wouldn’t know how to enable students to formulate their own learning outcomes.

13 When students find it difficult to gain insight into the material to be studied, I know ways to solve this.

14 Sometimes while working together with others on an assignment I get a sudden feeling that I’m learning a great deal from them.

15 If I find an assignment pointless I try to find out why this is.

16 I think it’s important that there are also personal aims linked to assignments.

17 When I’ve worked together with others on an assignment I don’t think about whether the co-operation was useful for me.

18 I sometimes get a sudden feeling that my method of work doesn’t suit the assignment.

19 Sometimes while working on an assignment I get a sudden feeling that I am learning something valuable from it.

20 When I study information I don’t pay much attention to how well I understand it.

21 When the co-operation between students turns out to be unproductive I don’t know any ways to solve this.

22 When I start on a text I first ask myself what I will need to do in order to study the text thoroughly.

23 I can’t tell whether a text to be studied will appeal to students.

24 When I work together with others I regularly think about what I learn from them.

25 Before I begin on an assignment I don’t have a clear idea of what I want to learn from it.

26 I think that feedback on my personal learning aims is unnecessary.

27 I can’t tell from a text how much effort it will take for students to understand it.

28 I see no reason to talk with others about the usefulness of working together on our studies.

29 When I’ve finished an assignment I don’t consider whether working on it has been useful for me.

30 I think that it’s important that students also learn from each other while they are studying.

31 If my personal involvement in the material to be studied were to be questioned I would think about this.

32 I know various ways in which students can increase their involvement in the material to be studied.

33 Before I begin on an assignment, I don’t ask myself whether I will learn more from it by working together with others.

34 I am interested in why I sometimes get very little out of my co-operation with others.

35 I am not interested in why I have an aversion to some of the texts I have to study.

36 If I can’t bring any structure into an assignment, I try to find out why that is.

37 When students don’t work systematically, I don’t know any ways to solve this.

38 If I find information difficult to understand I don’t try to find a deeper reason for this.

39 I find it helpful to talk with others about how one can gain an understanding of the texts to be studied.

40 I can tell whether an assignment corresponds to students’ learning aims.

41 When I’ve finished studying information I check for myself whether I’ve gone into enough depth.

42 When I’ve studied obligatory material I ask myself whether it aroused my interest.

43 When I have to study information I try to find out what I will find interesting about it.

44 Before I begin an assignment I don’t think about how I will introduce structure into it.

45 I know which assignments students will learn more from by working together.

Perceived Autonomy Support: The Climate Qustionnaires

Autonomy-supportive social contexts are hypothesised to facilitate self-determined motivation. This scale attempts to gauge learners’ perceptions of the classroom climate. The most relevant variant of this scale for autonomy researchers is probably the Learning Climate Questionnaire. It includes questions like:

My instructor listens to how I would like to do things

My instructor tries to understand how I see things before suggesting a new way to do things.

You can read more about it here:

link

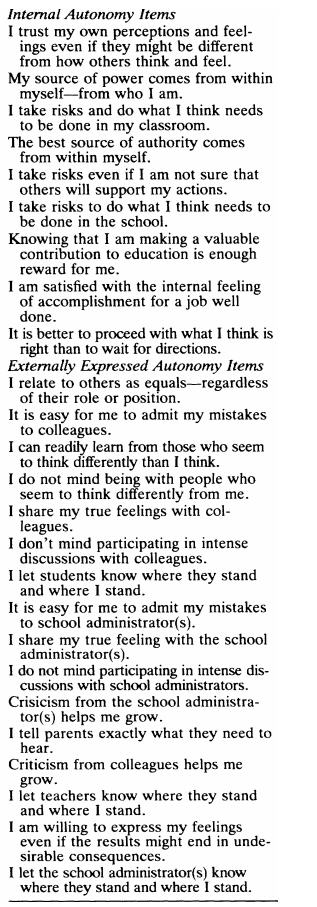

The Self-Empowerment Index

This is an instrument ‘designed to measures teachers’ internal sense of autonomy and how teachers express their autonomy to others.’ You can read more about it here:

Sandra Meacham Wilson Educational and Psychological Measurement The Self-Empowerment Index: A Measure of Internally and Externally expressed Teacher autonomy 1993; 53; 727. Available here: link

Some of the questions include:

Autonomy supportive versus controlling

In addition to the above there are also instruments looking at teachers. Below is a questionnaire to gauge the extent to which are ‘autonomy supportive’ or controlling. It includes 32 vignettes like the one below with four possible responses. Readers are asked to rate the appropriateness of each response.

A. Jim is an average student who has been working at grade level. During the past two weeks he has appeared listless and has not been participating during reading group. The work he does is accurate but he has not been completing assignments. A phone conversation with his mother revealed no useful information. The most appropriate thing for Jim’s teacher to do is:

1. She should impress upon him the importance of finishing his assignments since he needs to learn this material for his own good.

2. Let him know that he doesn’t have to finish all of his work now and see if she can help him work out the cause of the listlessness.

3. Make him stay after school until that day’s assignments are done.

4. Let him see how he compares with the other children in terms of his assignments and encourage him to catch up with the others.

You can read about it here:

Reeve, J., Bolt, E., & Cai, Y. (1999). Autonomy-supportive teachers: How they teach and motivate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 537-548.

Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)

This is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess motivation and learning strategies use by college student. From its manual (see below): ‘The motivation scales tap into three broad areas: (1) value (intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientation, task value), (2) expectancy (control beliefs about learning, self-efficacy); and (3) affect (test anxiety). The learning strategies section is comprised of nine scales which can be distinguished as cognitive, metacognitive, and resource management strategies. The cognitive strategies scales include (a) rehearsal, (b) elaboration, (c) organization, and (d) critical thinking. Metacognitive strategies are assessed by one large scale that includes planning, monitoring, and regulating strategies. Resource management strategies include (a) managing time and study environment; (b) effort management, (c) peer learning, and (d) help-seeking.’

You can find all 81 questions here. For more information you can read its manual:

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. Garcia, T. & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A Manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan.

Survey of Reading Strategies

The Survey of Reading Strategies was designed by Mokhtari and Sheorey and is used to measure adolescent and adult ESL learners’ metacogntive awareness and perceived use of strategies. You can read more about it here.

Others – descriptions forthcoming

Lai, J. (2001). Towards an analytic approach to assessing learner autonomy. AILA review, 15, 34-44.

Murase, F. (2007). Operationalising the Construct of Learner Autonomy: Preliminary Study for Developing a New Measure of Language

Learner Autonomy. In the Proceedings of the Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice.

Autonomy across the disciplines. Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan, October 2007. You can read this paper here.

References

Below are some potentially useful references to articles that have discussed evaluating autonomy:

Dam, L. & Gabrielsen, G. (1996). The acquisition of vocabulary in an autonomous learning environment – the first months of beginning English. In R. Pemberton, E.S.L. Li, W.W.F Or & H.D. Pierson (Eds.) Taking control: Autonomy in language learning, Hong Kong University Press, 265-280.

Dam, L. (2000). Evaluating autonomous learning. In Sinclair, B, McGrath, I & Lamb, T. (Eds.) Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: future directions. London: Pearson Education Limited, 48-59.

Mynard, J. (2004). Investigating evidence of learner autonomy in a virtual EFL classroom: a grounded theory approach. In J. Hull, J. Harris, and P.Darasawang (eds.). Research In ELT: proceedings of the international conference 9-11 April, 2003. School of Liberal Arts and the Continuing Education Center, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Thailand, 117-127.

Mynard, J. (2006). Measuring learner autonomy: can it be done? Independence, 37, pp3-6.

Reinders, H. & Lázaro, N. 2008 ‘The assessment of self-access language learning: practical challenges. ‘ Language Learning Journal, 36(1), 55-64. (Available from this website).

Reinders, H. & Lazaro, N. 2008 ‘Current approaches to assessment in self-access’. TESL-EJ Journal, 11:3, 1-13. (Available from this website).

Sinclair, B. (1999). More than an act of faith? Evaluating learner autonomy. In C. Kennedy (Ed.) Innovation and best practice. Harlow: Longman.

Vanijdee, A. (2003). Thai Distance English Learners and Learner Autonomy. Open Learning, 18(1), 75-84.