Free tools > Practical tips

Humanizing technology in language learning and teaching.

My latest position paper for Oxford University Press is out now. You can download it for free here.

The Key to Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulation, or the ability to monitor and regulate behaviour in the pursuit of one’s goals, is foundational to many positive life outcomes, such as health, wellbeing, social standing and financial security (Robson et al., 2020). In education too, the ability to engage in self-regulated learning (SRL) has been shown to have a significant impact on lifelong educational and professional outcomes (Panadero et al., 2017) in general, and language learing specifically (Csizér & Tankó, 2017; Dӧrnyei & Ryan, 2015; Seker, 2016). However, this ability does not come easily. It needs to be nurtured over a period of years, ideally throughout a learner’s educational life (e.g. from the primary to the secondary and tertiary levels) as well as across different subjects (Cohen, 2012). This process is often hampered by the significant differences in the ways in which SRL is understood, taught and supported, if indeed it is at all. These differences exist not only between educational levels and individual schools but also between teachers within the same organisation. One of the main causes of these differences is the inconsistent integration of SRL across the curriculum.The primary purpose of this paper is therefore to propose a framework for implementing and integrating the development of SRL. This requires a consideration of the ways in which organisations (schools, universities, training centres and the units within them, such as faculties, year levels, and self-access centres) establish their pedagogical aspirations and balance these with the regulatory, administrative and other requirements and constraints they operate under.

Successful implementation of SRL also requires an appreciation of the importance of the interrelationships between an organisation and its stakeholders; its leaders, its teachers, administrators, support staff, parents and the wider community. For it is only if the different parts of the organisation understand each other’s needs and work towards shared goals, that the integration of SRL across the curriculum is possible. This paper will introduce the Framework for SRL in three parts. In the first section readers are guided through a process of identifying needs, strengths and weaknesses, goal setting and monitoring of progress (itself an example of a self-regulatory cycle) from two perspectives: that of the individual teacher, and that of the wider organisation.

The second part of the Framework concerns the pedagogical implementation of SRL Starting from ways to motivate learners to self-regulate, to supporting them in developing the skills necessary for identifying learning needs, setting (broader) goals, making (specific) plans, selecting appropriate resources and strategies, engaging in meaningful practice, monitoring progress and engaging in self-assessment.

In the third part, the Framework considers how the practices at the organisational and the pedagogical level can be integrated. For example, one teacher’s insights from the process of implementing self-assessments may have implications across a programme, from highlighting the need for further staff development on this topic to a re-evaluation of the organisations’ testing practices. It is this ‘closing of the loop’ that helps to create long-term sustainable practices around the implementation of SRL.

You can download the position paper for free here

Using Technology to Motivate Learners

Technology continues to open up new opportunities for motivating language learners. Unlocking the considerable potential of technology depends on institutions, teachers, learners, and communities working together to understand how it can best be implemented in a specific context.

When technology is used with a clear understanding of the benefits it can offer and of the potential learning and motivation outcomes, it is more likely that its adoption will foster and sustain learner motivation. This paper summarizes key lessons learned from research and practice in the use of technology for motivating learners.

It contains a number of new insights that have emerged inrecent years. Many of the benefits of technology relate to its potential to create connections between the classroom and learners’ lives, interests, and experiences beyond it. With careful and consistent support, teachers can help learners

develop the skills and confidence to use technology effectively to manage and find personal meaning in their learning.

Taking an integrated approach to implementing technology into the curriculum and classroom practice will help to maximize its potential benefits and enhance

learner motivation. This requires careful management and coordination by all stakeholders, including curriculum developers, teachers, and administrative staff.

Support for teachers and learners is at the heart of realizing the potential benefits of technology for motivation and learning. Teachers need to be able to

develop their own skills in working with technology. Learners need appropriate opportunities that are driven by their needs and interests and give them the tools to assume greater responsibility for their own learning. The key messages in this paper are that:

• technology can have a significant impact on motivation by increasing learners’ sense of autonomy, relatedness, and competence

• technology can support learning in a wide range of both formal and informal learning spaces

• successful implementation of technology is always context-specific and requires integration into the curriculum and classroom practice

• the effective use of technology requires careful preparation and appropriate support for both teachers and learners.

You can download the position paper for free here

10 Rules for Encouraging Interaction In and Beyond the Classroom

At a time when learners are expected to move between different - often new - learning environments, how can we ensure they are able to participate actively? In this presentation I recently did for Cambridge University Press, I present 10 'rules' based on best practice and research.

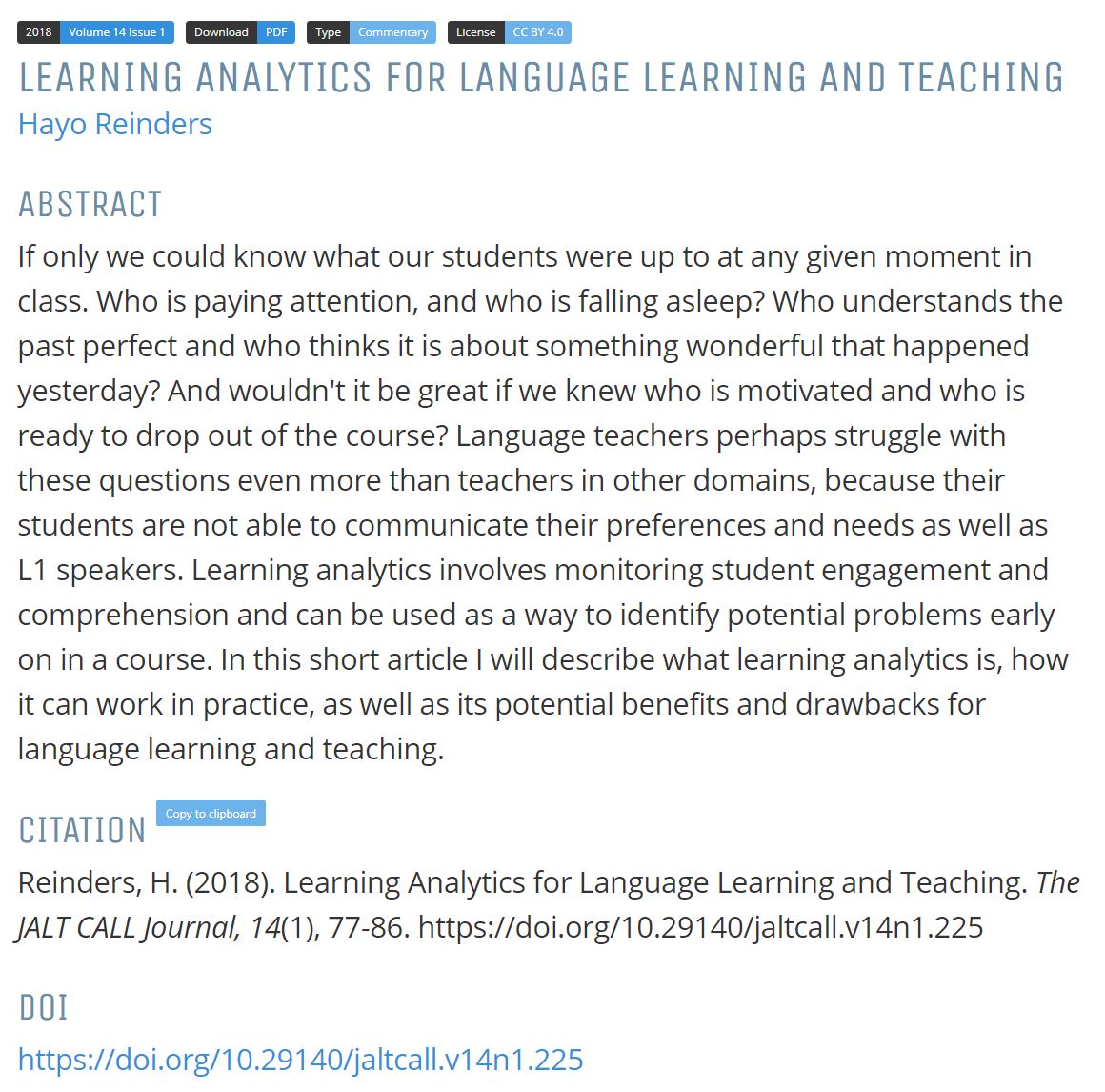

Learning Analytics for Language Teachers

Learning anaylytics and data mining hold tremendous potential for language education. However, to most teachers the topic may seem obscure, highly technical and far removed from classroom practice. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the short article below, I will show you how language data is accessible and of great use to teachers (and learners). The full reference is: Reinders, H. (2018). Learning analytics for language learning and teaching. Jaltcall Journal 14(1), p.77-86.

Here you can read the article.

Cambridge University Press Digital Day Q&A

We recently had a panel Q&A with CUP on digital teaching, with questions from people coming live from around the world. This was a lot of fun! The session was recorded and you can watch it here.

What is learner autonomy and why would I care about it?

Learner Autonomy is, first and foremost, a mindset. A way of thinking about learning as a journey where you decide where to go, and how to travel. You may occasionally hire a tour guide to explain about the local sights, but then you’re on the road again, to wherever the events and the people you meet take you. Sometimes you go directly to the next town, and sometimes you stop for a drink on the way. Sometimes you go to the museum, and sometimes for a hike in the mountains. Sometimes you read about the history of the sights, and sometimes you just soak up the atmosphere. Sometimes you feel great, and sometimes you are homesick. And sometimes, you just need a break.

Autonomy, then, is an intimately personal affair. It is about your life, about what you want to achieve, and what you enjoy. In this way, it is the only way to learn successfully in the long term. Because no one knows you better than you do, and no one can make your choices for you, autonomy requires you to get to know yourself better. Becoming autonomous is a process of discovery.

Because autonomy is about you and starts from within you, it cannot be forced upon you. You, and you alone, can make the decision to start this journey. But just as good travellers listen to others and learn from their experiences, good learners are not islands. They rely on others to offer insights, and occasionally, show them the way.

Autonomy is thus about freedom, both freedom from being told what to do, and the freedom to do what you think is best. Autonomy does not live happily in places without choice and it does not prosper in places where one part of the population is disadvantaged. Restrictions on what to learn or how to learn do not favour the development of autonomy.

Want to learn more? Join the free online Learner Autonomy LAB sessions

The Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE) promotes research, professional development, and best practice in developing lifelong and lifewide autonomous learning. We have an active community of practitioners and researchers and offer regular, free online sessions for professional development and to share ideas. You can read more about the upcoming schedule on the RILAE website (will go live by November 2017).

Free online course on facilitating workshops.

In support of my upcoming book, "The Accidental Teacher," I have created an online course on facilitating workshops which you can access here: